David Broomfield wrote a very comprehensive article in the Swiss Railways Society quarterly magazine, Swiss Express, for March 1993 on the history and proposed route of the Bergeller Bahn, with his permission, this page is an abridged version of that article.

The early history of the Bergeller Bahn is complex and confused, largely because of the number of promoters and the subsequent loss of plans and papers. The first idea was the result of a treaty signed by Switzerland with Germany and Italy permitting the construction of a transit route through the Gotthard. Before this Graubűnden had, since Roman times, been a favourite route between north and south and the local population did not want to lose the benefits this brought them. Unfortunately by the time they woke up to the threat the Gotthard route was going ahead. Furthermore it took 25 years to resolve the in-fighting between the interested parties, principally over whether to build a standard gauge line with international potential or a narrow gauge one to serve local needs. The delay was fatal to schemes with international potential and the Bergeller Bahn in particular.

Many early proposals for railways in Graubűnden envisaged a through route to Italy via the Maloja Pass, reached after crossing the centre of the Canton by way of the Sertig, Scaletta or Albula passes. A concession was granted by the Federal Government to Zschokke & Cie. Of Aarau for a narrow gauge route Chur – Thusis – Tiefencastel – Oberhalbstein – Julier or Septimer Pass – Maloja – Chiavenna, but financial support was not forthcoming. The Cantonal Parliament, tired of the delays, called for an independent report and appointed Robert Moser who would later be involved in the development of the Albula route. He exposed many weaknesses in the Zschokke proposals and they were forced to abandon the project but managed to hold on to the concession for the Maloja – Chiavenna section.

By 1897 this concession had still not been exploited and it was given to the Landquart – Davos Bahn in 1898, the year it became the Rhätische Bahn. The Landquart – Davos line had been financed by convincing the local communities along the route to provide a substantial subsidy in exchange for shares in the railway, but this was stubbornly resisted by the inhabitants of the Bergell. After completion of the Davos – Filisur link it became clear that any further extension would require Federal assistance as there were no more wealthy communities to be served.

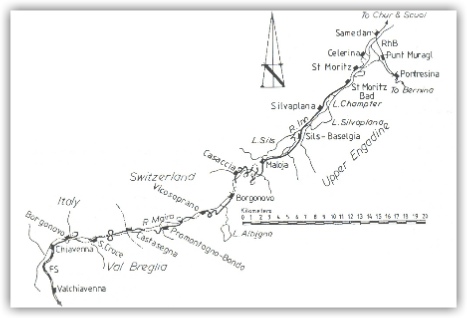

Proposed Route of the Bergeller Bahn

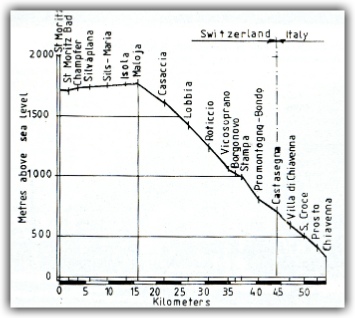

Gradient profile of an early scheme. This was part of the Scalettabahn and had a maximum gradient of 4.5%

This assistance was chanelled into the Disentis and Scuol lines and the Bergell line was deferred. A change of heart came over the people who, on 10th November 1912, voted a subsidy of Sfr 700,000 and this enabled the RhB to send engineers into the valley to evaluate the possibilities. Italy and Austria, seeing themselves at the opposite ends of a through route, Chiavenna to Landeck were very interested in the proposals, ostensibly for commercial reasons but more realistically for military purposes. It would have enabled them to support each other in the event of war. For similar reasons the Swiss military were not in favour of the proposals. This was the situation when war broke out and all work on the Bergeller Bahn was stopped.

The route was never finalised though some details of the project are available albeit with contradictions. Pre- World War 1 estimates of costs were in the region of Sfr. 60 – 70 million which would have doubled or trebled post war. Much of the expense arose in coping with the difference of 1486m between the maximum and minimum heights of the line whilst keeping to a ruling grade of 3% although 3.5% was considered for the steepest section between Maloja and Casaccia. The overall length would have been 67 km with the lowest altitude of 333m at Chiavenna and the highest of 1819m at Maloja. The steepest grade between St. Moritz and Maloja would have been 1.5% and 3% between Maloja and Chiavenna. The distance between St. Moritz and Chiavenna as the crow flies is only 42 km – less than two thirds of the planned length of the railway. There would have been at least 33 tunnels totalling 16 km, some 60 bridges and avalanche galleries and many other engineering works necessary to retain the mountain sides. About 70% of the line would have been curved with up to eight spiral tunnels.

After the war ended Italy and Austria showed no more interest in the line but the local communities, now aware of the railway and the tourists it would bring, were very keen to contribute. But it was too late, despite several attempts to revive the project, the RhB shared in the world’s economic crises and in 1936 the RhB no- longer sought to prolong the concession.

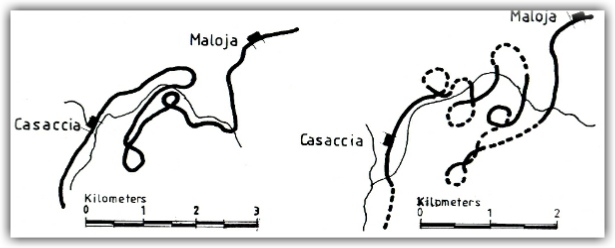

Alternative Routes for the Maloja Pass

The Route Described:

As at Scuol the exit track from St. Moritz was actually laid and crosses Via Serlas by a bridge before ending on a short embankment and acting as a head shunt. The line would then have entered a 1.6 Km tunnel before arriving at St. Moritz Bad. Keeping to the valley floor with beautiful views of the Upper Engadine it would have skirted the north side of Lake Champfer before reaching Silvaplana. It would have continued along the north shore of Lake Silvaplana and then swung southwards across the valley between the lakes, leaving the main road and crossing the Inn by a substantial iron bridge to arrive at Sils – Baselgia station, serving the two villages. It would then have run at the foot of the mountain slope along the southern shore of Lake Sils to reach Maloja. Until this point the route has been fairly gentle, but things change suddenly as the line drops down the Maloja Pass into the valley of the Orlegna river. The direct distance from Maloja to Casaccia is 3 km but the height differential is 357m corresponding to a gradient of 12%. To keep this to 3% would have meant lengthening the line to 12 km. The project description of this section is confused, talking of both two and four spiral tunnels, the later figure seeming the more likely. With the desire to keep costs down, increasing the gradient to 3.5% was certainly discussed, this would have reduced the length of the line by 2 km. Indeed, had this steeper grade been adopted over the whole line it would have saved 9 km but at the expense of reducing the permissible drawbar tonnages of the locomotives. The engineering works of all types on this section would have been massive as the line swung from one side of the valley to the other to loose height, crossing the Orlegna several times.

After Casaccia the river, which has now become the Maira, is crossed by a large bridge to allow the line to keep to the valley floor although many tunnels and bridges were still needed nearer to Vicosoprano. An alternative route map shows the line clinging to the western slopes of the valley. After Vicosoprano the Maira is crossed four times and another spiral tunnel is encountered before reaching Promotogno-Bondo – the RhB proposal shows two spiral tunnels here but speaks of one. A tunnel then leads under Bondo village and the Maira is crossed once more before arriving in Castasegna, which was to have had a four-berth loco. Shed with a 15m turntable. The line would then have crossed the border after another 300m and continued through a further pair of spiral tunnels to reach Santa Croce. A further spiral tunnel to avoid the rockfall area around Puiro would have bought the line to Borgonovo. After several more tunnels and another river crossing the line would have reached Chiavenna where it was undecided whether it would run straight in alongside the Italian standard gauge or tunnel under it to reach the other side.

The head shunt at St. Moritz station – all that was ever built of the Bergeller Bahn. It was modified when the road was widened and a new bridge built. The track ends up against the ventilation grill of an underground car park. This photo was taken in July 2016 during the rebuilding of St. Moritz station. As part of this rebuilding the head shunt will be removed, and there will then be no physical evidence of the Bergeller Bahn.

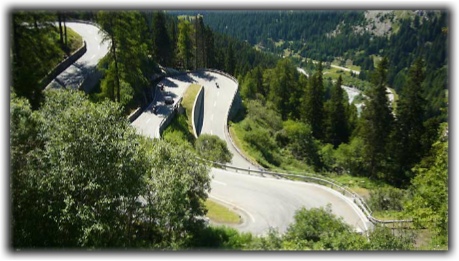

The Maloja Pass today

So that is what might have been, it would have been very spectacular as it made its way down the Maloja pass. But is it really only in the past? The RhB is still expanding its network, the Vereina line was opened in 1999 and there is now talk of the Davos to Arosa tunnel. So who knows, the Bergeller Bahn may still one day become a reality.

Page updated 13th August 2018